Liskov Substitution Principle Explained

Last updated on November 13, 2022 pm

This article gives a quick intro to the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP), why it’s important, and how to use it to validate object-oriented designs. We’ll also see some examples and learn how to correctly identify and fix violations of the LSP.

What is the LSP?

At a high level, the LSP states that in an object-oriented program, if we substitute a superclass object reference with an object of any of its subclasses, the program should not break.

Say we had a method that used a superclass object reference to do something:

1 | |

This should work as expected for every possible subclass object of SuperClass that is passed to it. If substituting a superclass object with a subclass object changes the program behavior in unexpected ways, the LSP is violated.

The LSP is applicable when there’s a supertype-subtype inheritance relationship by either extending a class or implementing an interface.

1 | |

This makes sense intuitively - a class’s contract tells its clients what to expect. If a subclass extends or overrides the behavior of the superclass in unintended ways, it would break the clients.

How can a method in a subclass break a superclass method’s contract? There are several possible ways:

- Returning an object that’s incompatible with the object returned by the superclass method.

- Throwing a new exception that’s not thrown by the superclass method.

- Changing the semantics or introducing side effects that are not part of the superclass’s contract.

Java and other statically-typed languages prevent 1 (unless we use very generic classes like Object) and 2 (for checked exceptions) by flagging them at compile-time. It’s still possible to violate the LSP in these languages via the third way.

Why is the LSP Important?

LSP violations are a design smell. We may have generalized a concept prematurely and created a superclass where none is needed.

Future requirements for the concept might not fit the class hierarchy we have created.

If client code cannot substitute a superclass reference with a subclass object freely, it would be forced to do instanceof checks and specially handle some subclasses.

If this kind of conditional code is spread across the codebase, it will be difficult to maintain.

Every time we add or modify a subclass, we would have to comb through the codebase and change multiple places. This is difficult and error-prone.

It also defeats the purpose of introducing the supertype abstraction in the first place which is to make it easy to enhance the program.

It may not even be possible to identify all the places and change them - we may not own or control the client code. We could be developing our functionality as a library and providing them to external users, for example.

Violating the LSP - An Example

Suppose we were building the payment module for our eCommerce website. Customers order products on the site and pay using payment instruments like a credit card or a debit card.

When a customer provides their card details, we want to

- validate it,

- run it through a third-party fraud detection system,

- and then send the details to a payment gateway for processing.

While some basic validations are required on all cards, there are additional validations needed on credit cards. Once the payment is done, we record it in our database. Because of various security and regulatory reasons, we don’t store the actual card details in our database, but a fingerprint identifier for it that’s returned by the payment gateway.

Given these requirements, we might model our classes as below:

1 | |

1 | |

1 | |

A different area in our codebase where we process a payment might look something like this:

1 | |

Of course, in an actual production system, there would be many complex aspects to handle. The single processor class above might well be a bunch of classes in multiple packages across service and repository layers.

All is well and our system is processing payments as expected. At some point, the marketing team decides to introduce reward points to increase customer loyalty. Customers get a small number of reward points for each purchase. They can use the points to buy products on the site.

Ideally, we should be able to just add a RewardsCard class that extends PaymentInstrument and be done with it. But we find that adding it violates the LSP!

There are no fraud checks for Rewards Cards. Details are not sent to payment gateways and there is no concept of a fingerprint identifier.

PaymentProcessor breaks as soon as we add RewardsCard.

We might try force-fitting RewardsCard into the current class hierarchy by overriding runFraudChecks() and sendToPaymentGateway() with empty, do-nothing implementations.

This would still break the application - we might get a NullPointerException from the saveToDatabase() method since the fingerprint would be null. Can we handle it just this once as a special case in saveToDatabase() by doing an ***instanceofv check on the PaymentInstrument argument?

But we know that if we do it once, we’ll do it again. Soon our codebase will be strewn with multiple checks and special cases to handle the problems created by the incorrect class model. We can imagine the pain this will cause each time we enhance the payment module.

For example, what if the business decides to accept Bitcoins? Or marketing introduces a new payment mode like Cash on Delivery?

Fixing the Design

Let’s revisit the design and create supertype abstractions only if they are general enough to create code that is flexible to requirement changes. We will also use the following object-oriented design principles:

- Program to interface, not implementation

- Encapsulate what varies

- Prefer composition over inheritance

To start with, what we can be sure of is that our application needs to collect payment - both at present and in the future. It’s also reasonable to think that we would want to validate whatever payment details we collect. Almost everything else could change. So let’s define the below interfaces:

1 | |

1 | |

PaymentResponse encapsulates an identifier - this could be the fingerprint for credit and debit cards or the card number for rewards cards.

It could be something else for a different payment instrument in the future. The encapsulation ensures PaymentInstrument can remain unchanged if future payment instruments have more data.

PaymentProcessor class now looks like this:

1 | |

There are no runFraudChecks() and sendToPaymentGateway() calls in PaymentProcessor anymore - these are not general enough to apply to all payment instruments.

Let’s add a few more interfaces for other concepts which seem general enough in our problem domain:

1 | |

1 | |

1 | |

1 | |

And here are the implementations:

1 | |

1 | |

1 | |

Let’s build CreditCard and DebitCard abstractions by composing the above building blocks in different ways.

We first define a class that implements PaymentInstrument:

1 | |

1 | |

1 | |

Though CreditCard and DebitCard extend a class, it’s not the same as before.

Other areas of our codebase now depend only on the PaymentInstrument interface, not on BaseBankCard.

Below snippet shows CreditCard object creation and processing:

1 | |

Our design is now flexible enough to let us add a RewardsCard - no force-fitting and no conditional checks.

We just add the new class and it works as expected.

1 | |

And here’s client code using the new card:

1 | |

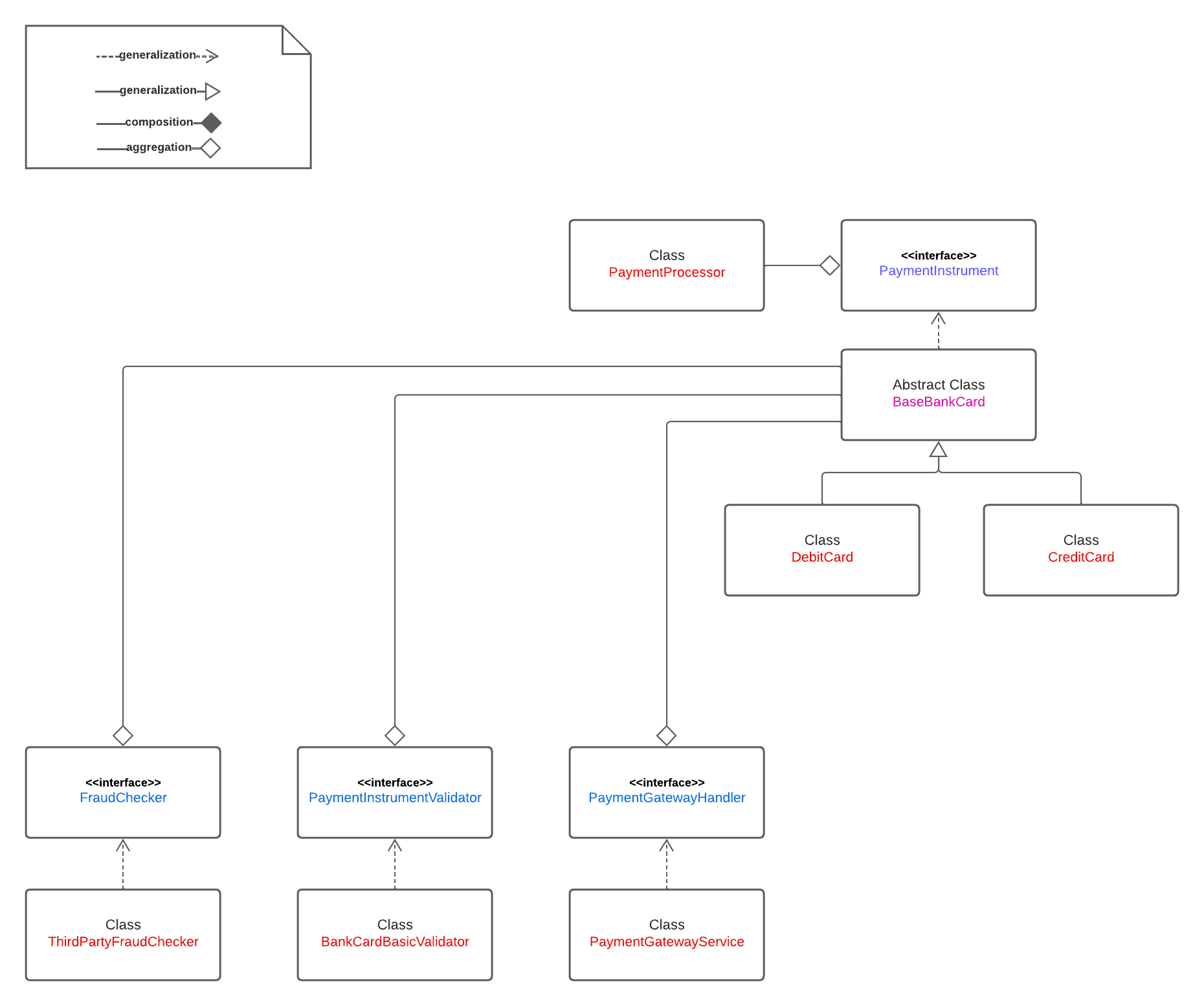

Here is the final class diagram

Advantages of the New Design

The new design not only fixes the LSP violation but also gives us a loosely-coupled, flexible set of classes to handle changing requirements.

For example, adding new payment instruments like Bitcoin and Cash on Delivery is easy - we just add new classes that implement PaymentInstrument.

Business needs debit cards to be processed by a different payment gateway? No problem - we add a new class that implements PaymentGatewayHandler and inject it into DebitCard.

If DebitCard’s requirements begin to diverge a lot from CreditCard’s, we can have it implement directly instead of extending BaseBankCard - no other class is impacted.

If we need an in-house fraud check for RewardsCard, we add an InhouseFraudChecker that implements FraudChecker, inject it into RewardsCard and only change RewardsCard.collectPayment().

How to Identify LSP Violations?

Some good indicators to identify LSP violations are:

Conditional logic (using the instanceof operator or object.getClass().getName() to identify the actual subclass)

in client code empty, do-nothing implementations of one or more methods in subclasses throwing an UnsupportedOperationException or some other unexpected exception from a subclass method.

Consider java.util.List

Is this an LSP violation? No - the List.add(E e) method’s contract says implementations may throw an UnsupportedOperationException. Clients are expected to handle this when using the method.

Example output

Starting payment processing for customer Mehrdad with creadit card number 1234-1234-1234-1234-1234

Running fraud checks against third-party system

Fraud checks passed

Sending details to payment gateway

Credit card payment successful!

Starting payment processing for customer Mehrdad with rewards card number 1234-1234-1234-1234-1234

Updating rewards balance

Rewards card payment successful!